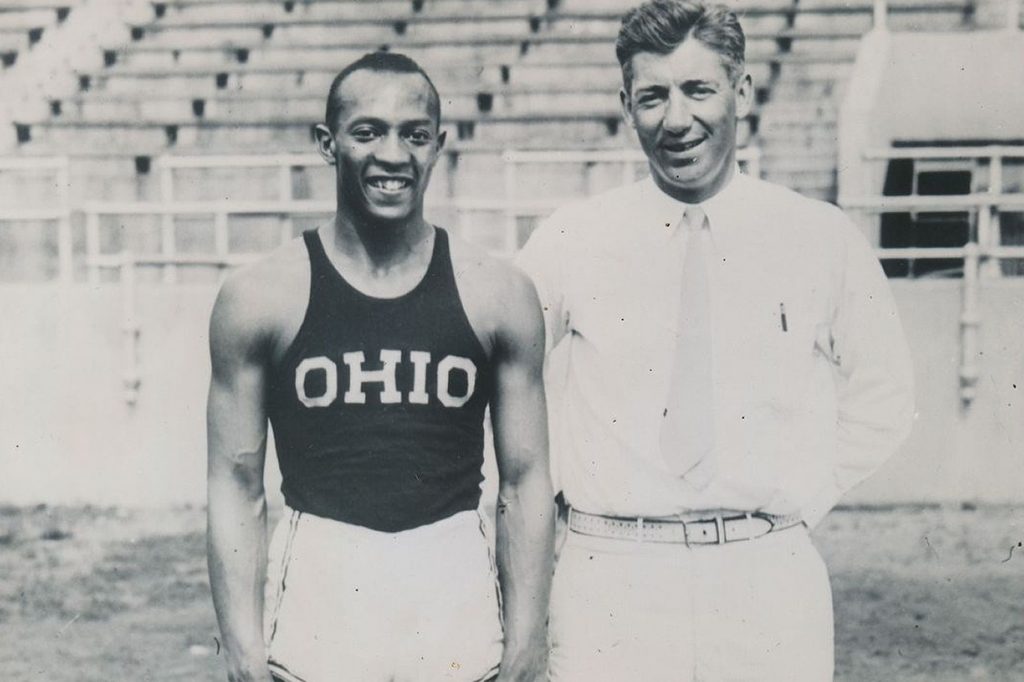

(World Athletics) Six weeks after Jesse Owens enjoyed his stunning day of days, accumulating six world records in the space of 45 minutes at the 1935 Big Ten Championships in Ann Arbor, Michigan, came something of a day of reckoning.

At the AAU Championships in Lincoln, Nebraska, the man who had accomplished the greatest single-day feat in track and field history was eclipsed in his two main disciplines, the 100m and the long jump, by the one rival he feared: his fellow Alabaman, the largely forgotten Eulace Peacock.

On today’s 90th anniversary of Owens’ phenomenal afternoon at Ferry Field – when he equalled the world record for 100 yards before setting new global marks in the long jump (world’s first eight-metre leap), 220 yards flat and 220 yards hurdles (plus 200m equivalents en route) – a look back in time reveals that it was far from a straight trajectory from his trailblazing deeds on May 25, 1935 to his show-stealing quadruple gold medal-winning performance at the Berlin Olympics in 1936.

Peacock got the better of the pride of Ohio State University in five sprint races in six days later in the summer of 1935, building up a sequence of seven successive wins in all events by the time of the 1936 indoor season.

He also got under the skin of a rival who was always a close friend, and with whom he formed a business partnership in later years – to such an extent that Owens proclaimed: “I don’t know whether I can defeat him again.”

As it happened, the fickle hand of injury was to beat the unfortunate Peacock on the road to Berlin – unlike Owens on that fateful day at Ferry Field nine decades ago.

“I reckon I should have backache more often”

A World Athletics Heritage Plaque honouring the great man’s historic feats now stands at the Ann Arbor track, unveiled last year by Owen’s proud granddaughter, Marlene Dortch.

And yet, on the day, Owens had to be helped out of a car and into the dressing room by his Ohio State teammates. He had badly injured his back in a fun fight with fellow students five days earlier.

Even after a steaming hot bath and the application of “a big swab of hot liniment,” the 21-year-old was unable to perform his usual warm-up routine: a 440 yards jog, followed by a calisthenics routine. “I couldn’t even jog, let alone stretch,” he recalled.

“I don’t think you should chance it today,” Owens’ coach, Larry Synder, urged him as he made his way gingerly towards the start of the 100 yards, at 3.15pm. “It’s not worth the risk.”

Owens insisted he should at least “try” the first event – then proceeded to blast down the track in 9.4, equalling the world record held by Frank Wykoff, a member of the victorious US 4x100m relay teams at the 1928 and 1932 Olympics.

Ten minutes later he took one attempt in the long jump, aiming for a white handkerchief placed alongside the sandpit at 7.98m, the world record distance set by Japan’s Chuhei Nambu in 1931.

To the astonishment of all 12,000 in attendance, not least himself, Owens soared past it, landing at 8.13m, a mark that stood unmatched for a quarter of a century, until Ralph Boston jumped 8.21m in 1960.

The man christened James Cleveland Owens, who became “Jesse” after a teacher asked for his name and misinterpreted “JC”, then further etched his adopted identity into track and field history by clocking 20.3 for 220 yards and 22.6 for the 220 yards hurdles.

At 4pm, his ailing charge having left the world record book in tatters, Snyder asked how his back was. “Coach, I reckon I should have backache more often,” Owens replied. “I feel great.”

“One of the greatest double upsets in the history of track”

That feeling was wearing thin by the time Owens lined up for the 100 yards final at the AAU Championships in Lincoln on July 4.

Signs of fatigue were evident – not least in San Diego eight days previously, when Peacock appeared to have edged Owens in a tight finish to a 100 yards race.

Eyebrows were raised when the verdict was given to Owens, an official confiding to Peacock: “You won the race but they’d already carved Jesse’s name on the trophy.”

Like Owens, his senior by 11 months, Peacock was both a native Alabaman and also the son of a sharecropper and grandson of a slave. In 1933 he set a New Jersey scholastic long jump record of 7.43m that stood until 1977, when the future 110m hurdles world record-holder Renaldo Nehemiah leapt 7.59m.

A sophomore at Temple University, he had gained the moniker “the Philadelphia Flyer” after winning the 1935 US 100m title ahead of Olympic 100m silver medallist Ralph Metcalfe and Owens and then equalling the 100m world record of 10.3 jointly held by Metcalfe, Percy Williams and Eddie Tolan at the Bislett Stadium in Oslo.

“At 6ft and 180lbs, Peacock was stronger than Owens,” Donald McRae wrote in his brilliant study of Owens and another of his great friends, the boxer Joe Louis, In Black & White. “Rather than floating across the track, he propelled himself down the cinders with driving aggression.”

That driving aggression was too much for Owens in Lincoln. Peacock beat him in the 100m heats in 10.2, a 2.22m/s following wind denying him an outright world record, then finished comfortably ahead of Metcalfe and Owens in the final, this time clocking 10.2 with 3.47m/s wind assistance.

Peacock also got the better of Owens in the long jump, 8.00m to 7.98m, completing his own personal day of days – or, as Arthur Daley put it in The New York Times, “one of the greatest double upsets in the history of track”.

Peacock proceeded to rack up six sprint wins over Owens. Lawson Robertson, the Scottish-born head coach of the US Olympic track and field team, told reporters: “Peacock is the fastest and most consistent starter of all our sprinters. He also has a better finish than Owens.”

Owens himself reflected: “Eulace looks like he’s more than caught up now. I’ve already reached my peak and he is just now reaching his. I don’t know whether I can defeat him again.”

“What might have been”

Peacock tore his right hamstring in a 4x100m heat at the Penn Relays at the start of the 1936 outdoor season. It popped again at the US Olympic Trials in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He finished 10th in the long jump and broke down in the 100m final.

Owens swept to victory in both events and on to lasting glory as the hero who dealt a telling blow to Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich’s warped Nazi ideology with his four gold medals (100m, 200m, long jump and 4x100m relay) at the Berlin Olympic Games.

Peacock never made it to an Olympic Games but accepted his fate with grace. “What can you do?” he shrugged. “Sure, I was disappointed, but you can’t spend your time wondering what might have been.”

After the Second World War, Peacock went into partnership with Owens, running a wholesale meat packing business in Harlem and the Bronx, the All Star Trading Company.

He died in 1996, aged 82. Owens died in 1980, aged 66.

Simon Turnbull for World Athletics Heritage